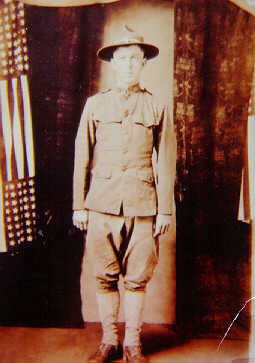

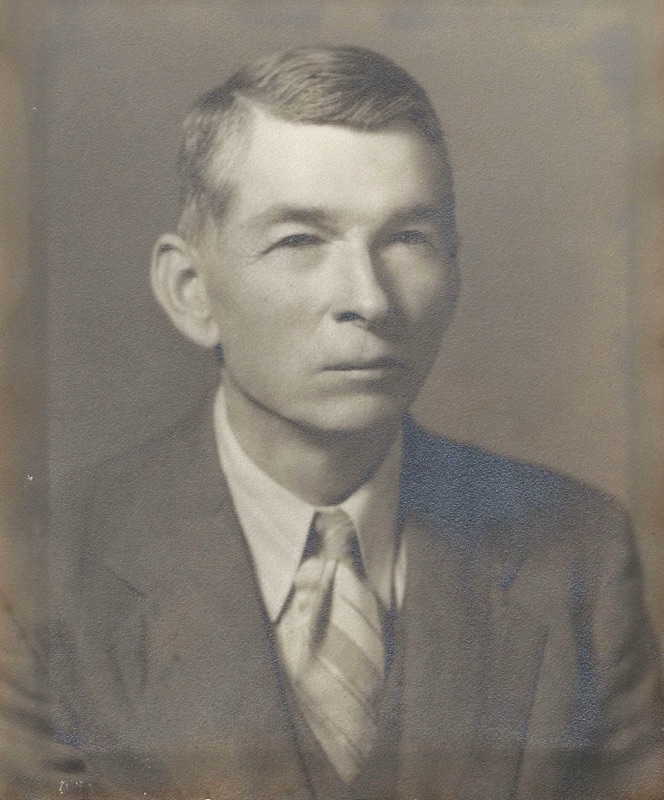

To his children he was Papa.

To his brothers he was Buddy.

To nieces and nephews, he was Uncle Buddy.

To his wife, Mr. Joe.

A man known by many names, each one stitched to a different part of his life.

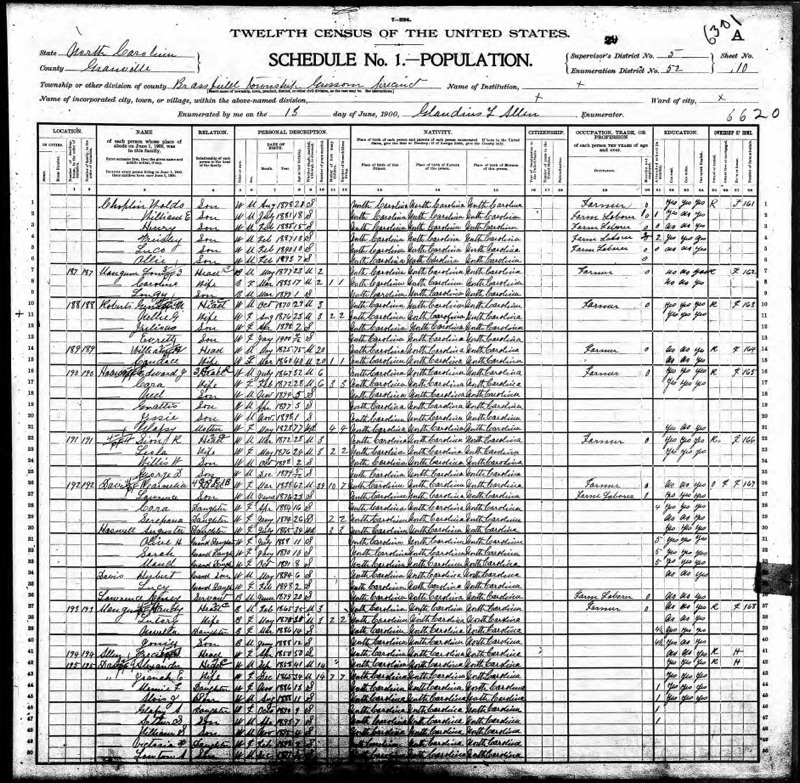

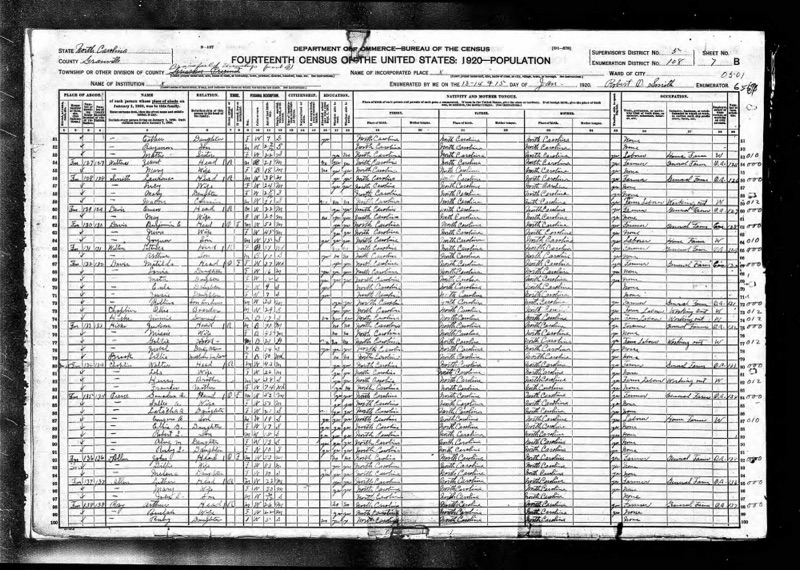

Joseph was the son of Allen Davis, age 49 when Uncle Buddy was born on February 12, 1885 and Francis Tyson “Ticyanne” or “Ticy” Choplin, age 39. A day he shared with his brother Albert ‘Luico’ Choplin who was born on February 12, 1888.

Uncle Buddy was 13 years old when he first shows up on an official record in the 1900 census, He lived in Brassfield Township in Granville County, North Carolina with his mother and 5 of his 7 brothers, worked as a farm laborer, and also attended school.

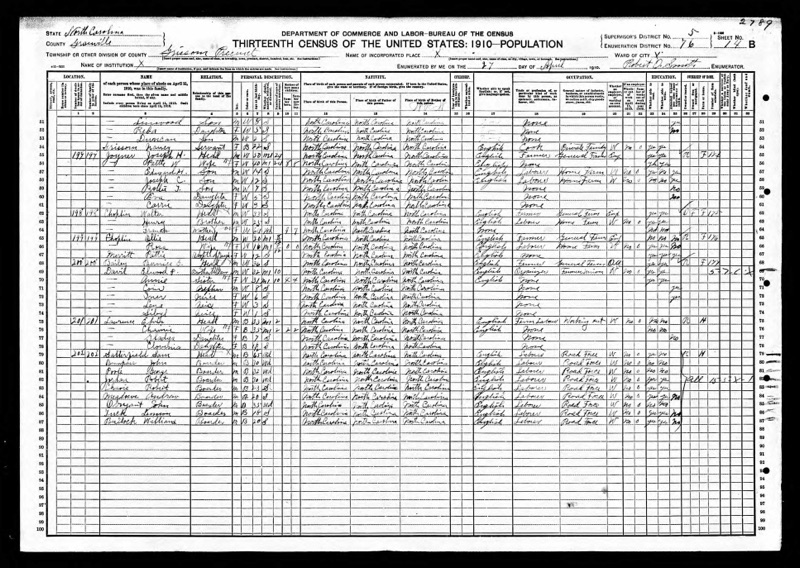

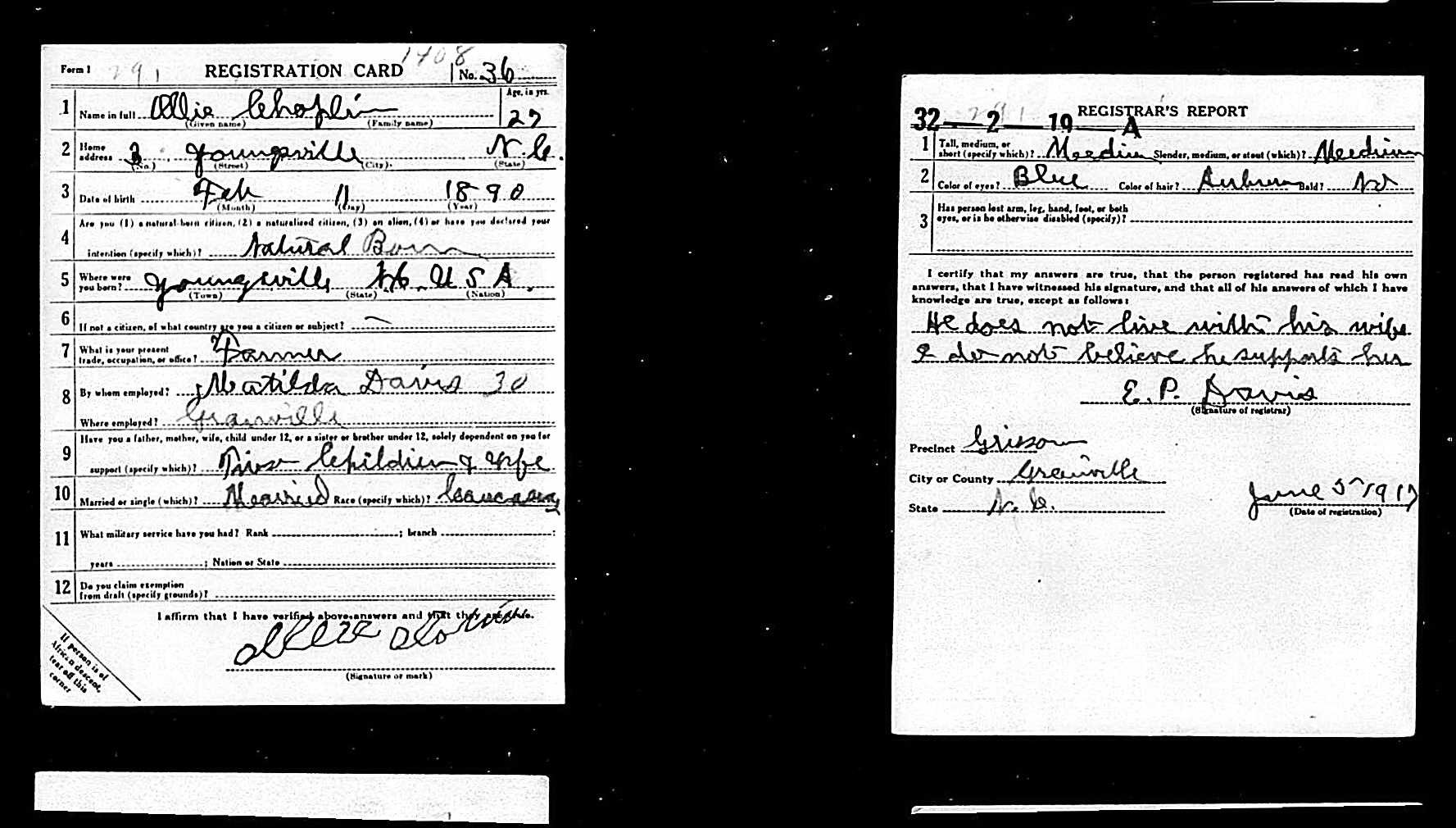

It’s not known when, but not long after this census record was taken he moved north toward Henderson where he continued to working as a farm laborer.

Work of His Hands 🌾🏪

After Uncle Buddy moved to Warren county in his late teens and he worked as a sawmill hand, farmer, and grocery store clerk. It was on one of his trips to the town of Henderson for supplies that he met Ms. Elizabeth Jane Abbott, or Lizzie as she was known; his future wife.

Left: Joseph Presley Choplin and wife Elizabeth "Lizzie" Jane Abbott Center: Albert "Luico" Choplin and wife Ella Ayscue Right: Walter James Choplin and wife Lela Smith Front: Twins Billie & Betty Choplin; Walter & Lela Choplin's daughter

Left: Joseph Presley Choplin and wife Elizabeth "Lizzie" Jane Abbott Center: Albert "Luico" Choplin and wife Ella Ayscue Right: Walter James Choplin and wife Lela Smith Front: Twins Billie & Betty Choplin; Walter & Lela Choplin's daughter

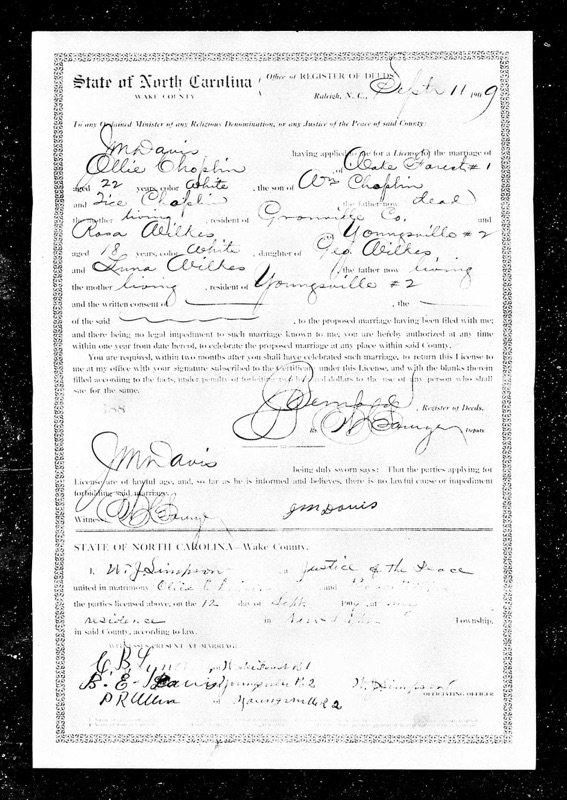

A Wedding in a Buggy 🚜💍

On January 21, 1906, Joseph married Elizabeth Jane “Lizzie” Abbott in a way no courthouse could ever outshine. According to their daughter Effie Choplin Wright, Uncle Buddy and Ms. Lizzie were administered the Rites of Matrimony while seated in a horse drawn buggy parked along Shepherd’s Road between Sandy Creek and Vicksboro in Warren County, near where their future home would stand. I can’t help but to wonder if this was a spur of the moment wedding; it just felt like the right time? Or was it a romantic moment Uncle Buddy had planned in front of the property they would one day call theirs? I think it would be perfect either way, but it will remain a moment only Mr. Joe and Ms. Lizzie experienced, a moment in time that only belongs to them.

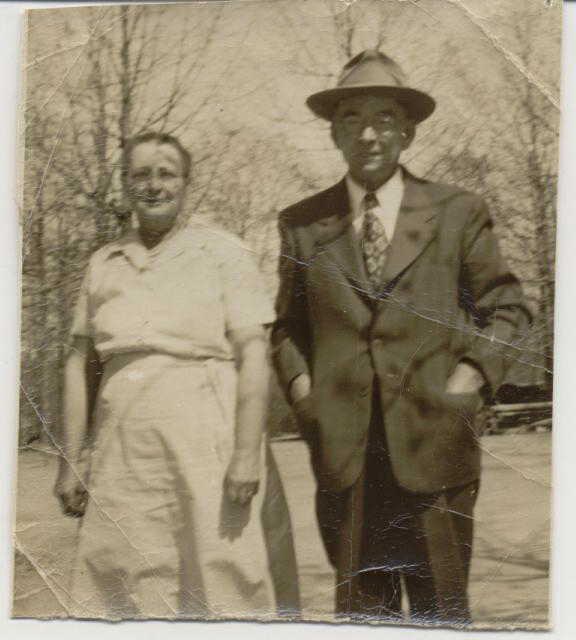

Joseph Presley Choplin and wife Elizabeth "Lizzie" Jane Abbott Late 1950s

Joseph Presley Choplin and wife Elizabeth "Lizzie" Jane Abbott Late 1950s

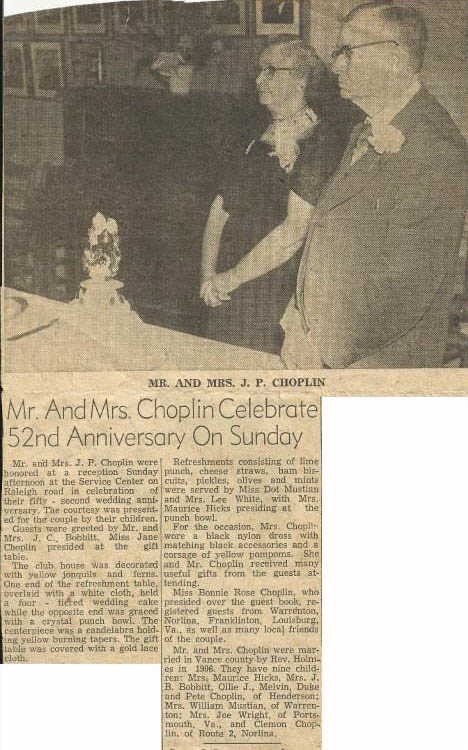

In 1958 the couple made the local newspaper when their children had a celebration for their 52nd wedding anniversary seen below. A milestone fewer while make. When Uncle Buddy passed away in 1965, they had been married 59 years!

A Household Full of Life 👶

Uncle Buddy and Ms. Lizzie first bundle of joy would arrive in March of 1907. Eleven more would follow over the next 24 years.

- Sadie Elizabeth Choplin — March 25, 1907

- Joseph J. Choplin — February 15, 1909

- Effie Green Choplin — March 3, 1911

- Melvin Thomas Choplin — September 21, 1913

- Linwood Allen Choplin — June 20, 1917

- Oliver “Ollie” Johnson Choplin — September 6, 1918

- Clemon Barden Choplin — March 10, 1921

- Infant son

- Marvin Peter Choplin — June 9, 1925

- Mary Joseph Choplin — July 26, 1926

- Hunter Duke Choplin — September 1, 1929

- Dorothy Louise Choplin — September 27, 1931

A household that size does not stay quiet. It hums, it rattles, it breathes. Joe loved his children deeply and was a present, steady father. They loved him just as deeply in return. Perhaps his aim was to be the kind of father he himself may not have had, creating in his own home the security and care he believed a family deserved.

The family’s life was rich, but it was not without sorrow. On May 17, 1910, Uncle Buddy lost his only son at the time, three year old Joseph J. Choplin. The cause of death is unknown. Baby Joseph’s resting place, marked with the words “Asleep in Jesus,” can be found in the Community Cemetery in Vicksboro.

Tragedy visited twice more; in 1917 when their son Linwood Allen Choplin passed away in infancy. The circumstances of his death are also unknown. And in 1923 with the loss of another baby boy at birth. These quiet losses, so common in that era yet no less devastating, were part of the unseen burdens Joe and Lizzie carried while raising the family that followed.

The Day the County Held Its Breath 📰

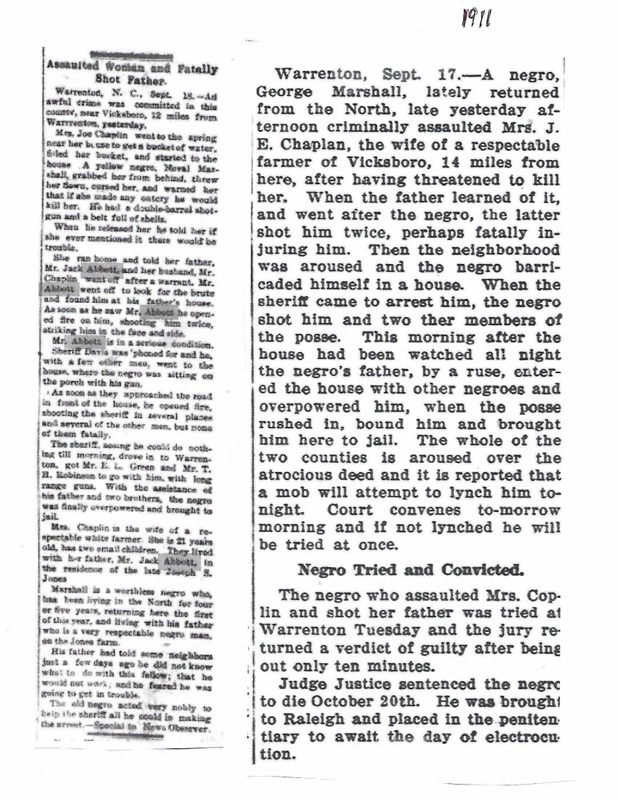

On March 10, 1921, Mrs. Lizzie and Uncle Joe were living with her parents. Mrs. Lizzie had gone down to the spring near their house and was returning home with water when a man, George Marshall, grabbed her from behind and held her at gunpoint. He eventually released her, and she ran home, telling her husband and father, Jack Abbott.

Jack went searching. Joe went to fetch the police.

Jack found Marshall at his father’s house. Gunfire erupted as Jack approached the house. Jack Abbott was shot in the face and side, left in critical condition. When Sheriff Davis and a group of arrived, Marshall fired again, wounding the sheriff and some of the men with him, though not fatally. A standoff followed through the night. The next morning, Marshall’s own father and brothers disarmed him and held him down so the sheriff could arrest him.

The county was in uproar. Officials feared lynching mob would storm the jail. Marshall was tried the next day in Warren County, found guilty after ten minutes of deliberation, and sentenced to death. He was transported to Raleigh to await electrocution on October 20, 1921.

Through it all, Uncle Buddy’s role stands steady and clear. He sought law, not vengeance.

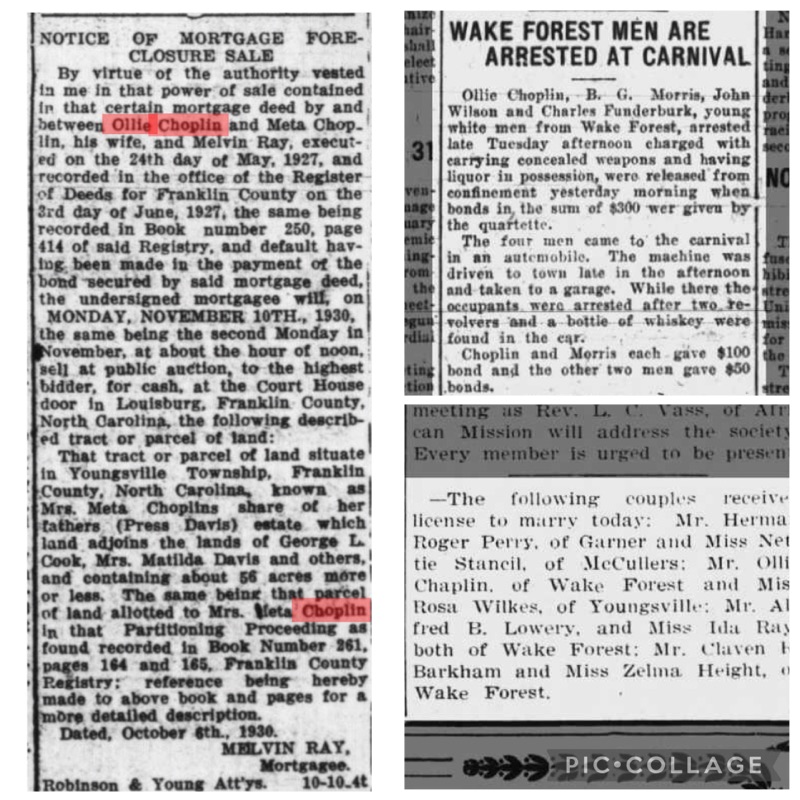

Franklin Times 1920

Franklin Times 1920

Faith, Family, and Reputation ⛪

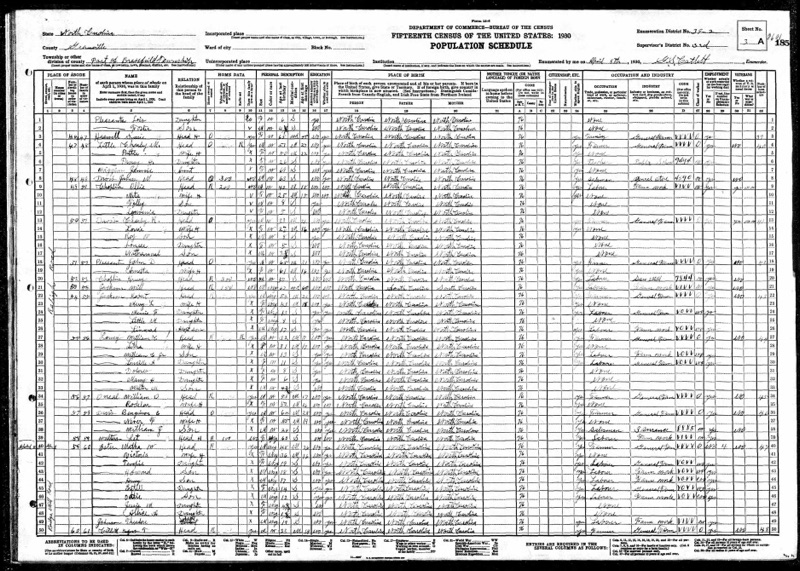

Uncle Buddy would purchase a farm on Shepherd’s Road where he moved his family. They raised cash crops such as tobacco, corn, and cotton. During the 1930s and 1940s he opened a grocery store next door to his home in rural Warren County and owned several rental houses in Henderson. By every account, Uncle Buddy was a successful businessman who built his life with steady hands and long days.

Joseph Choplin's farm house located on Shepards Road in Warrenton

Joseph Choplin's farm house located on Shepards Road in Warrenton

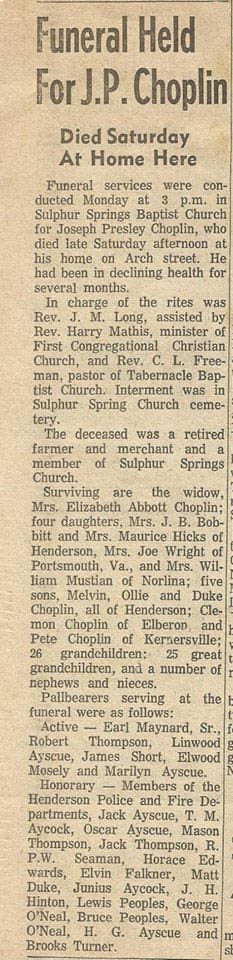

Uncle Buddy was a proud Christian and an active member of Sulphur Spring Baptist Church, attending regularly and encouraging others to do the same. He was known as a loving father, respected husband, and well liked man in the community.

Final Resting Place

It seems that Uncle Buddy moved to Henderson when he retired from farming. The address listed on his death certificate is 324 Arch Street in Henderson.

Joseph “Uncle Buddy” Choplin is buried in Warrenton at Sulphur Spring Baptist Church beside his loving wife. At the time of his death he had 26 grandchildren and 25 great-grandchildren. A number of Henderson Police officers and Firefighters attended his funeral. What an amazing legacy to leave!

If you are connected to the Choplin, Abbott, or Davis families, or have photographs, documents, or stories about Uncle Buddy and Mrs. Lizzie, please share in the comments!